The exploded assembly to the right shows an accessory sold alongside Chelsea Technologies Ltd’s portable Single Turnover Active Fluorometry device, or "LabSTAF" for short. The accessory in question allows for automated sample exchange (via the hose connections up top), as well as gentle stirring to ensure interrogation of the entire sample during testing.

The Problem

The problem with the Sample Stirring accessory device was that the final assemblies had an uncharacteristically high rejection rate, failing during the quality control process due to damaged gearboxes. I was tasked with investigating the root cause and undertaking corrective actions.

The Investigation

Upon inspection, the failures were being caused by the Stirrer Arm interfering with the underside of the Main Body. This resistance to the arm was increasing the forces through the Shaft and damaging the smallest gear in the gearbox.

Initial suspicions for this interference lay with the externally manufactured Main Body component, however, CMM inspection found that all dimensions fell within their required bounds. Next, the off-the-shelf components were investigated but they too met their stated tolerances.

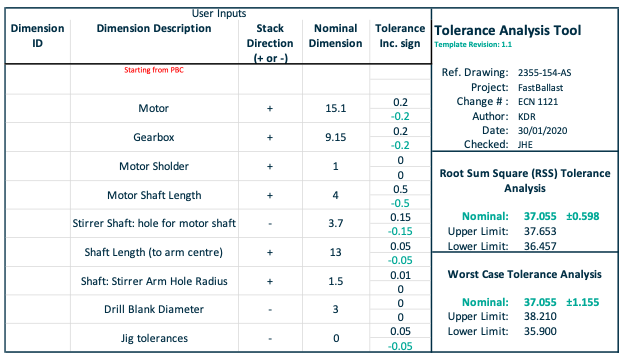

With all parts looking acceptable my focus switched to the design itself. An RSS tolerance analysis confirmed the real-world rejection rate, showing that the tightly controlled dimensions of the Main Body were not able to offset the relatively large tolerances in the off-the-shelf components.

Sadly, the fix wasn’t as simple as adjusting tolerances on the components within our control, loosening them would result in the Stirrer Arm protruding beyond the maximum allowable distance and increasing them would have pushed several of the tolerances beyond the reasonable limit for their machining process.

.png)

The Solution

Counterintuitively, the solution implemented was to reduce the nominal distance between the bottom of the Main Body and the Stirrer Arm. With a tweak to the position of the grub screw on the Shaft component, it was possible to add a level of adjustability to the design which allowed the assembly to absorb much larger tolerances.

A production jig was also introduced to the assembly process to control this new adjustable design, guaranteeing repeatable results every time.

.png)

.png)

The Result

These solutions reduced the rejection rate to almost zero, adding adjustability that allowed for tighter control and greater consistency of the assemblies produced.

The few remaining ‘rejections’ were also now detectable earlier in the assembly phase, before significant time investment, and it was now possible to swap the Motor in a problematic assembly for an alternative with a more favourable tolerance stack-up in a small scale ‘selective assembly’ process, reducing scrap to almost nil.