A 2021 analysis of the issues faced by Active Humidification

The human respiratory system is a humid place, with your breath carrying water vapour wherever it goes. Numerous processes rely on this moisture for their daily activities and it helps to clear mucous and other nasties which might find their way into your system.

Typically, the air we breathe is fairly ‘dry’, so to keep humidity levels in your system high the tiny hairs in your nasal passages trap a majority of the moisture in the air you exhale before it leaves, ready to be collected by your next inhale and reused. This process is effective, if you want an example of just how effective think back to the last time you woke up after a night of sleep with a blocked nose. Your mouth doesn’t retain any moisture, so you wake up feeling worse for wear with your mouth dry, lips chapped, and desperate for a drink.

When a patient is in intensive care unable to breathe under their own control, they are intubated. That is, they have tubes passed down their throat and into their lungs which bring in air from a Ventilator, entirely bypassing their nasal passage. Ventilators run off a combination of ‘Medical Air’ and ‘Oxygen’, both of which are pure and dry. Over time the flow of these gases wicks away moisture faster than the patient’s body can produce it, drying out their respiratory system and potentially leading to a number of severe or even life-threatening complications.

To combat this ‘drying’ effect a medical device known as a ‘Humidifier’ is introduced to the system. This device passes the patient’s air over a chamber of lightly boiling water, providing moisture and conditioning the air as it is carried through to the patient roughly 1.5meters of tube later.

.png)

Plastic breathing tubes aren’t good insulators, which poses two problems. The first is that even in the warm environment of a hospital’s Intensive Care Unit the patient’s humid air supply will cool down fast. To combat this there is a coiled ‘Heater Wire’ running the length of the breathing tubes which the Humidifier uses to keep the air at the required 37degrees.

The second problem is condensation. In the same way that water from the air inside your home condenses on the cold windows, the humid patient gas condensates against the walls of the breathing tubes. This is a major problem because over time (days in the best case, hours in the worst case) this condensation builds up within the patient’s breathing tube and if left unattended will block the air supply entirely.

This is a known problem which the manufacturers of these Humidifiers are working to fix, however, in the meantime what nurses must do is lift the tubes every couple of hours to tip the condensation back into the Humidifier, all the while knowing the very severe risk of any water travelling the wrong way, towards the patient’s lungs.

There are three trains of thought when it comes to solving this problem:

-

Adjust the layout of the internal Heater Wire to give a nice, even, consistent heat along the walls of the tube so that it keeps the surface warm and stops condensation forming.

-

Make the tubes out of an insulating material, such as closed-cell foams.

-

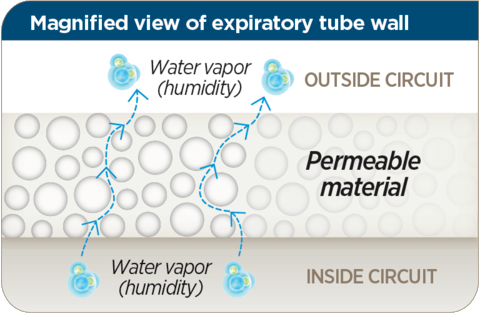

Use a slightly porous material that allows condensation to slowly pass through the walls out into the surrounding room.

Option 1 is a sound solution. Even distribution of a coiled heater wire along the tube reduces the temperature differential between the walls and the airflow, however, it is limited by manufacturing costs. The processes involved require exponentially more expensive specialist machinery and that shows. Hamilton’s H900 Breathing Circuits are a great example, integrating the heater wire into the walls of the tubes, but they are significantly more expensive than a company such as Intersurgical who take a more basic approach, this makes it difficult for them to compete.

Option 2 is where things start to get interesting. F&P’s new MR950 specific tubes are a work of art. They take a thin film smoothbore internal tube, then they wrap it with an inflated pillowy insulating layer which is sealed using a bead of more rigid plastic, integrated into which is the heated wire. They combine incredible insulation with a perfectly distributed heater wire and still manage to retain remarkable flexibility, the product is unmatched in the industry. But these tubes are exceedingly expensive, potentially retailing at around £90 per set of single-use tubes. Arguably only someone as dominant in this market as F&P could pull this off, and only because they also offer the best-in-class tube for Option 3 as their ‘cheap’ alternative.

The concept for Option 3 is to use a slightly porous material for the tubes, one whose structure is fine enough to retain air molecules and bacteria but porous enough to allow any condensation to simply pass through and out of the system. It works incredibly well and requires no intervention from nurses/doctors to ‘drain’ the condensation from the system and the tubes can be manufactured and sold at a significantly lower cost than Options 1 or 2. The market offering for Option 3 is limited, with F&P holding the patent since it was first conceived, however, the patent ends sometime in 2021 so expect to see some new players in the field.

This article is intended to provide a background into the issues faced by the manufacturers of Active Humidification Devices and is written based on knowledge I gained whilst working in the field. During my time as an Electromechanical Development Engineer I explored many of the solutions mentioned above, producing various prototypes which fall under both Options 2 and 3, attempting to utilise cheaper methods of manufacturing to create tubes with similar performance to F&Ps Evaqua system.

The results were varied, with few prototypes making it to trial production runs, but the in-depth knowledge gained from the process allowed progress to start on an exciting new competitor which is soon to make it to market. To learn more about that project please head over to my article ‘Semipermeable Respiratory Tubes’.